I wanna tell you about a book I really like. It’s going to sound like the opposite of that to start with.

I think that the cover to this volume is too artistically executed. I think it’s so good that it does the story a disservice.

I looked at this cover, fresh from a review copy envelope. I thought “they do know we’re a pro-women site, right?”

Because I was not on the ball, I was taken in by the spotlight. I became the audience to these poses. Looking at these girls, in the spotlight: unconsciously, I recognise patterns from the Look, It’s A Female newspaper character designs that made me so uncomfortable when I was wee. Like this barmaid in an Andy Capp strip.

Lips! Tits! Hips! And whatever else in between. Literally and metaphorically spot-lit. Back in time, I’m eight, I’m looking for what designates “a grown woman”. The assumption is: The Bellybuttons is a book about girls being sexxxay.

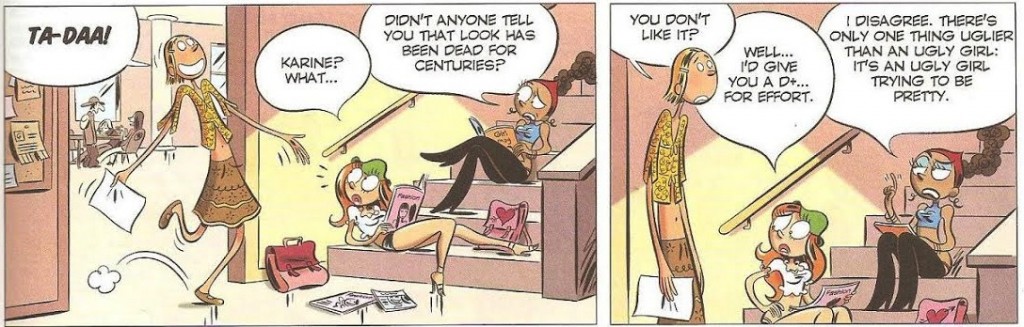

To be fair, that’s correct. But it’s turned all around to become (drumroll) social commentary: it is a story about girls. Two of whom are being, on purpose, sexxxay. In those ways that we learn to be. They’re also mean. The titular “Bellybuttons”–so called because their are pierced and visible, presumably–work very closely with the Queen Bee rules. Be beautiful, lean in, male attention is a victory, female peers are your (undeserving) competition. They work to be the cover girls of their own lives.

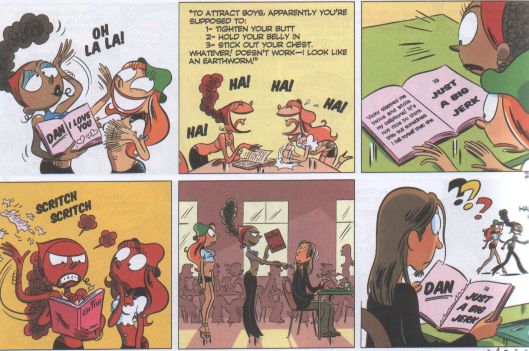

Delaf & Dubac take pains to gently, slowly, unfurl evidence of the labour of beauty. Through gag strips and teen romance capers and hijinks, we’re shown how much time and effort Bellybuttons Vicky and Jenny put into being “good enough” to be “popular.” And they are popular–they easily attract many, many handsome, socially powerful or well-made boys. The admiration, or traditional resentment and eye-rolls, of their girl peers is necessary too. Of course. Teen Movie popular, as well as actually socially sought-after.

An easy joke would be: these girls are pathetic, and the work they do to attract sexualised attention is useless, so we laugh. Gargling the rich cream of seeing failure and humiliation in somebody whose power you can’t comprehend. It would be easy to be mean spirited, and small, and grow in on yourself as you say something about sluts. I don’t say “easy” because it’s inviting to despise and belittle people, but because power is enticing and belittling people gives the illusion of embiggening–empowering–yourself.

I would not blame any consumer, especially any teenage girl consumer, for looking at this cover and retreating. Making a face. Resenting, and burning inside. I hear from Cinebook that Bellybuttons has yet to find the english-language fanbase it deserves (honestly, it really does deserve) and I’m not surprised, not one bit, because I at least would never have picked up this book alone. I am too tired of “seeing told” that this is how to be a woman. I don’t want to have to suck in and push out. I don’t want to have to bend my spine and stand on tip-toes when I’m not alone with my computer screen, second-hand jogging bottoms and Cassey Ho. I don’t want to have to consider any of these things because they’re simply not relevant to the womanhood that is mine, but I have felt practically all of my life that I must consider these things. Because they are how a person says “I’m female” and sees reward. I don’t know what the reward is. I can’t pinpoint where I got this impression. I can say that this is why I considered Cartoon Network commissioning Mimi Yoon’s Powerpuff cover so desperately regressive.

I did not look at the Bellybuttons’ cover with new, objective, attentive eyes until I had read two thirds of the book; confused and tentative about how much I was both liking, and not hating, the experience. Let’s look again now.

The art encourages the viewer to look at Jenny and Vicky. They’re posed to invite admiration (let’s hash that out in comments, but this is their motivation as established within the book). The “spotlight”–this is one two-dimensional illustration, ceci n’est pas une spotlight–highlights these two characters within an eye-leading circle, and within eye-catching lighting. Three focussing elements. Their facial features are exaggerated and enhanced by bright eyeshadow–four. Vicky is actually pushing Karine OUT of the area of attention, and her removal is mirrored by Jenny’s half-pictured satchel on the other side of the spotlit area. Artistically, Karine’s presence could barely be better suppressed. Once the comic has been read, it becomes a fantastic image! It represents almost every theme in the book. But before you’ve been given that context…

…I don’t know. Maybe this is my embarrassing prejudice only. But it did not feel inviting.

The title of this volume is “Who Do You Think You Are?” Very teen-issues. An aggressive challenge/a question asked in compassion. Exactly the kind of question that causes flinching and biting back and all of the negative cat’s cradle emotional navigation that so many people abdicate from with, “well, she’s a slut and a BITCH.” This is where we’re supposed to be, reading Bellybuttons. We’re shown how to dismantle our anger. We’re shown how to navigate the idea that our stereotypes and prejudices aren’t real. We’re gently introduced to the idea of being better than our weaknesses and acknowledging the humanity of mean people. The humanity of people who play by rules we don’t like.

“We” being judgemental teenagers in social pain who won’t admit they know better, I guess. There’s this amazing uncomfortable internal unfurling that comes with someone saying really seriously “you’re too good to fall back on that.” Pains are taken to let you feel tenderly enough for Jenny and Vicky, as well as put-upon, kind Karine, that you don’t become sharp with vengeance. You can deal with the harmful things they actually do in the story, and you can let go of the harmful things it maybe feels like they do to you conceptually.

Relax.

Jenny and Vicky don’t get attention only from vain, glorious cool boys and built, jerk-ass jocks. They get attention from good boys, kind boys, floppy hair boys. Boys who are your platonic friends, boys who’d never think to say you can’t throw baskets with them because you’re just a girl. Reasonable boys are attracted to J and V! Your good bros are excited by the product of long, steady-handed, expert hours of beauty work. You don’t have to wear mascara to get a boy. You don’t have to wear mascara ever. But respect the effort that artistry takes.

Karine, our tall and non-glamorous everygirl, is annoyed to be abandoned mid-game once her boy pals learn Vicky and Jenny want their attention. Does she dehumanise her (at this point, ex-) friends? Does our understanding of these boys regress? It progresses. Repressed/oppressed girls need to see that applied prettiness does not invalidate the women behind it, or the good men in front of it. Even if the glossy girl is thoughtless. Even if she’s cruel.

It’s hard to feel sympathy for the mean girl until you see her hit by a car. Lila Fowler waited for our well-wishes until her royal teenage husband died jet-skiing. For goodness’ sake! Who cares how “misunderstood” Lana Weinberger turned out to be, when six books ago she was accusing sweet, lonely girls of buying friends and calling new hairstyles “pus yellow”? When you’re writing teenage characters in school-based hierarchies, choosing to humanise the traditional monster after their damage is done is a dangerous game. Your reader might be hurting too much to listen.

The Bellybuttons introduces Jenny and Vicky as they’re writing a love letter to John John, the hottest boy in school. That’s Mr J. John. John, John John. They address their letter to “John,” because calling him by his surname sounds cooler. Eyes full of exuberance!

This letter is full of heartfelt admiration–for John’s material possessions. They’re so expensive! So up to date! These girls are wild for his purchased hipness! You can laugh at them straight away if that’s what you need, but the joke is too funny, too widely targeted to be actually spiteful. They really mean it. They really value these things. This is a character constructed of accepted coolness, valued in-universe for how cool he is. Understood outside the book by how cool he is. High School student with a motorcycle. Don’t pretend you don’t understand what John John means. I’ve read popular romantic adventure novels with that protagonist and loved it. You like the trappings, you’re shallow if you like the trappings, but you like the trappings. The trappings are everything. Jenny and Vicky LOVE the trappings. Jenny and Vicky are honest. And John John appreciates that.

If you can stand spoilers, check out these later-volume out-takes:

Volume one has subtlety on its side (watch carefully for hints when you see Jenny and Vicky’s homes during the strip that covers their morning routines), but lays strong foundations for revelations. Of course, it’s not exactly helpful to suggest that tough backstory mitigates horrible behaviour. It’s not progressive to imagine that sexually active teenagers must be running from their problems. And this book is not stupid enough to draw such a blunt line through all of it’s creators’ hard work. Are Vicky and Jenny even sexually active?

Bravado is what gets young and inexperienced people into trouble. Also older ones, and so on. But–

Bravado, and failing to consider other people as more than the simplifications you keep in your head. The Bellybuttons uses cartooning of elastic flair–expressive on every character–to reveal the complexity that MUST be in other people. Even in High School. Even the magazine-glossy ones. Even… in YOU.