Content warning: this article contains discussion of sexual abuse, including paedophilia.

The history of fantasy and science fiction has no shortage of colourful figures. In some cases, of course, “colourful” can be used only in a somewhat euphemistic sense. It is therefore with requisite air-quotes that I introduce one of the most colourful men working in contemporary fantasy: Theodore Beale, better known under his pen-name of Vox Day.

The author behind such books as A Throne of Bones, The Last Witchking, and The Altar of Hate, Day is known less for his fiction and more for his online commentary. Ever the attention seeker, he has the habit of fastening, lamprey-like, onto controversial Internet movements. He aligns himself with Gamergate, but is of dubious popularity even amongst Gamergaters. He marches alongside the Sad Puppies campaign, but Puppy leaders Larry Correia and Brad R. Torgersen have distanced themselves from him: “I’m Churchill, Brad is FDR,” says Correia. “We wound up on the same side as Stalin.”

Torgersen, meanwhile, has a more apt comparison: he has nicknamed Day “The Kurgan,” after the barbaric villain from Highlander.

Day describes himself as a “Cruelty Artist with a rather vicious sense of humor.” His admirers argue that “Vox Day” is a shock-jock persona used by Theodore Beale when he feels the need to stir up debate. In everyday Internet parlance, then, Vox Day is a troll—which is about the only way that his more extreme comments can even begin to be justified.

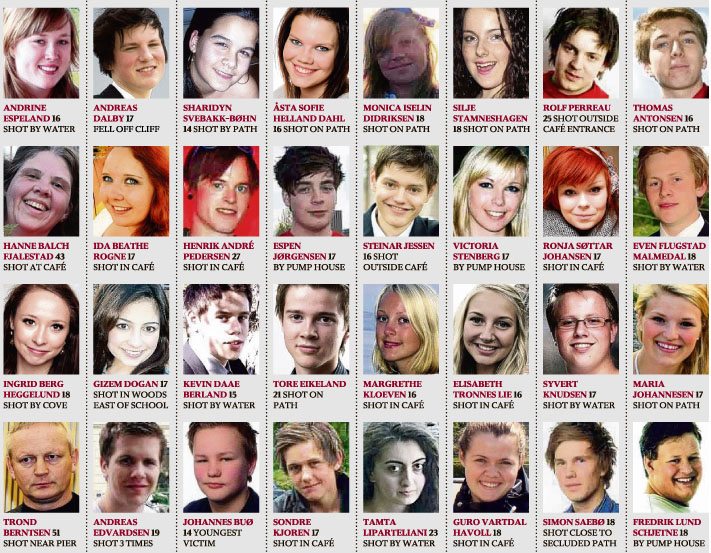

To pick just one example, we have this tweet from November in which Day invokes the mass murder carried out by Anders Breivik:

Day elaborated upon his views in the following discussion. “Breivik is not a nutcase,” he wrote. “He was found to be sane. You call him a murderer, the future will call him a hero.”

“The average age of his victims was 20,” Day continued. “They were mostly adult quislings. Your opinion is irrelevant. War is here.”

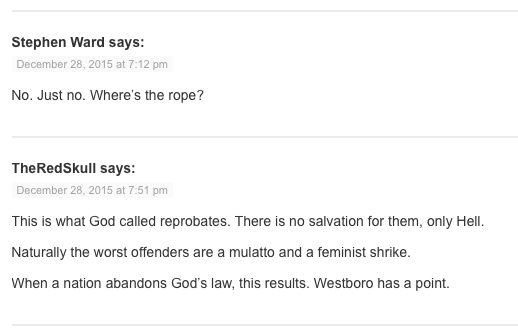

The above tweet about Breivik is one of more than a hundred postings from Vox Day to have been collected at Fundies Say the Darndest Things, a website dedicated to chronicling absurd statements from extremists of various political stripes. The intent of the site is primarily humorous, as its title suggests, but even its regular contributors often find the quoted material disturbing.

“He’s fucking around about this less than normal lately,” opines FSTDT owner Distind on the topic of Vox Day. “You don’t say ‘Anders Breivik will free EU’ without implying people need to die.”

Blue Versus Pink

Vox Day is eager to apply his hardline political views to his chosen genres of SF and fantasy. Day’s writing identifies two categories of science fiction, “Blue SF” and “Pink SF”:

Pink SF is the dominant form of science fiction today. Or rather, more properly, the currently dominant form of SyFy. It is necrobestial love triangles. It is using the superficial trappings of science fiction or fantasy or war fiction to tell exactly the same sort of goopy, narcissistic female-oriented story that has already been told in ten thousand Harlequin novels and children’s tales and Hollywood comeuppance fantasies.

Pink SF is an invasion. Pink SF is a cancer. Pink SF is a parasitical perversion. Pink SF is the little death that kills every literary subgenre.

[…]

So what, in contrast, is Blue SF? Blue SF is a return to the manly adventure fiction of the past. Blue SF says “fuck that” to strong independent female protagonists who ride rainbow-farting unicorns and flex their non-existent muscles when they aren’t being mounted by corpses and canids. Blue SF says “fuck that” to sexual equality, salutes la difference, and doesn’t deign to throw bones to women who might feelbad [sic] that their oh-so-tender feelingses isn’t being gently massaged. And Blue SF says “fuck off” to every idiot of either sex who whines about it being too this or not enough that.

Day’s supporters have eagerly adopted this pink/blue dichotomy. Amongst them is Daniel Eness, who lists ten tell-tale signs of pinkness in science fiction; these include rejection of Christianity, celebration of “sexual deviancy” and support for “the anti-scientific myth of human equality.”

The Day-Scalzi Feud

As you can see, Day is not exactly shy about condemning his contemporaries in the SF field. His favourite target is, by a sizable margin, John Scalzi.

As you can see, Day is not exactly shy about condemning his contemporaries in the SF field. His favourite target is, by a sizable margin, John Scalzi.

Hard as it may be to believe these days, but Vox Day and John Scalzi were not always such grievous foes. Back in 2008, Scalzi actually afforded Day a guest spot on his blog. This was not enough to bridge the considerable ideological rift between the two men, however, and Day subsequently developed a vendetta against Scalzi that reached embarrassingly petty levels.

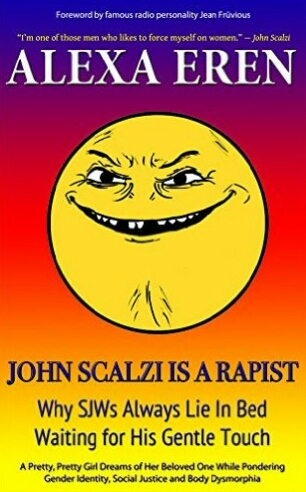

In 2012, Day published a blog post entitled “John Scalzi is a rapist.” This accusation is based on Scalzi’s “Fan Letter to Certain Conservative Politicians,” a clearly satirical piece of writing designed to highlight unjust treatment of rape victims under US law. Unperturbed by such pesky things as context, Day remains proud of this supposed dirt that he has managed to dig up on his arch-foe.

Later on, one of Day’s followers published a book also titled John Scalzi is a Rapist under the pseudonym Alexa Eren—a dig at author Alexandra Erin, who had previously written a book poking fun at Day’s hatred of Scalzi. I do not believe that the author of this volume ever stepped forward, but the book was inevitably endorsed by Vox Day.

These attempts to smear Scalzi as a rapist come across as little more than juvenile name-calling. Other instances, meanwhile, show that Day is serious in his effort to pin sex crimes on science fiction authors whom he dislikes.

In 2014, the SF world was rocked by the full revelation of Marion Zimmer Bradley’s complicity in the child abuse carried out by her husband Walter Breen. Vox Day saw a prize opportunity, and wasted no time in using the scandal to attack “Pink SF”:

This is the true heart of Pink SF/F. This is the twisted moral perspective they have been trying to push on science fiction readers as being imperative for more than three decades. This is the shamelessly hedonistic worldview they have been trying to assert as the pinnacle of the literary subgenres with their odes to dinoporn revenge and necrobestial multicultic rape fantasies.

Keep this in mind when the social justice warriors wag their fingers and lecture society on the burning need for tolerance and acceptance. This is what they seek to tolerate and accept.

Notice how Day uses Bradley’s crimes to smear contemporary SF/F authors. He makes a jab at Rachel Swirsky’s Nebula-winning “If You Were a Dinosaur, My Love” by mentioning “odes to dinoporn revenge,” and presumably has Twilight in mind when he brings up “necrobestial multicultic rape fantasies.” Elsewhere in the article, without providing any actual evidence, he suggests that other members of SFWA were personally involved with Breen and Bradley’s crimes.

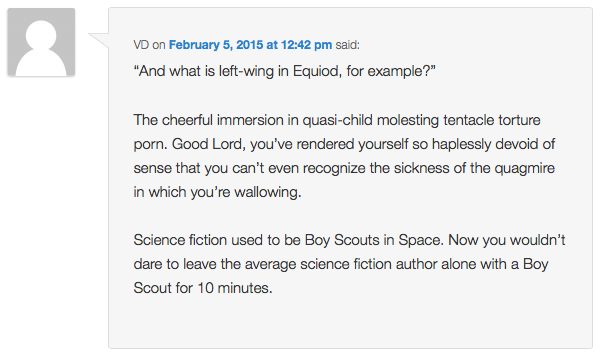

Day was prepared to make the most of this supposed connection between “Pink SF” and child sexual abuse, as can be seen in this post about the Hugo Awards and the Sad Puppies controversy:

So for those of you inclined to Puppy-kicking, I encourage you to think twice before you decide to take their side. Because you’re going to find yourself publicly associated with things far darker and more depraved than anything you ever accused the Puppies of being or doing. If you are determined to fight award recommendations in order to defend child molesters, then there is something seriously wrong with you.

What, exactly, did he mean when he predicted that people would be publicly associated with child molestation simply for criticising the Sad Puppies campaign? What did he have up his sleeve when he wrote these words…?

Daniel Eness and “Safe Space as Rape Room”

Vox Day’s secret weapon turned out to be “Safe Space as Rape Room: Science Fiction Culture and Childhood’s End,” a five-part essay by Daniel Eness. This was posted on the official blog of Day’s publishing company Castalia House in December 2015, with one instalment going up each Thursday.

The final chapter was published on New Year’s Eve, making the series just, just, eligible for the 2016 Hugo Awards—which, thanks to the introduction of new regulations in 2017, will be the final Hugos that Day can sweep using his bloc-voting tactics.

Daniel Eness’ series was clearly timed to serve as a parting gift: Vox Day’s last word to the awards that he had decided to destroy. And sure enough, when Day came to assemble his slate for the second Rabid Puppies campaign, Eness’ essay was present and correct as a Best Related Work candidate.

The first two chapters in the series, entitled “Pedophilia in Science Fiction – Introduction” and “The Vocal Enablers,” focus primarily on two child molestation scandals that occurred within science fiction and fantasy fandom. The first of these is the case of Walter Breen and Marion Zimmer Bradley; the second is that of convention-runner Ed Kramer, who was convicted of molesting teenage boys.

Eness associates a number of well-known authors with these scandals. He repeats eyebrow-raising statements by Harlan Ellison, Darrell Schwitzer and Anne McCaffrey, all of whom defended Kramer. He also discusses rumours about Arthur C. Clarke having sexual relations with teenagers, and recounts how Robert A. Heinlein left SF fandom in solidarity with the child molester Walter Breen (there is a good, balanced discussion of this last incident here).

After this, however, Eness starts to scrape the bottom of the barrel. The essay repeatedly attacks Vox Day’s old enemy John Scalzi, its main accusation being that Scalzi took too long to expel Ed Kramer from SFWA. Apparently realising that this is a little weak, Eness falls back on out-of-context quotations such as Scalzi’s “now famous admission to being a rapist.” Vox Day’s gross misrepresentation of Scalzi’s satirical post is repeated three times in the series.

As well as science fiction authors with only the vaguest connections to paedophilia, we find paedophiles with only tangential relation to science fiction. David Asimov, son of Isaac, was prosecuted for owning child pornography; he may have reproduced this material using inheritance money from his father. But as Eness provides no evidence that the elder Asimov was ever aware of his son’s predilections, it is hard to see the relevance of this sordid affair.

Eness then lists horror director Victor Salva, who molested a twelve-year-old boy in the 1980s; nowhere does he explain how Salva is connected to the circle of SF writers that included Asimov, Heinlein, and Clarke.

“I tipped the SF Chronicle when [Victor Salva] was arrested,” says Christopher Daley in response to the essay. “I can assure you Salva had nothing to do with fandom at all.”

Taking on Samuel R. Delany

The first post in Eness’ series also introduces the topic of Samuel R. Delany. In particular, it quotes this notorious statement made by Delany in 1994:

I read the NAMBLA [Bulletin] fairly regularly and I think it is one of the most intelligent discussions of sexuality I’ve ever found. I think before you start judging what NAMBLA is about, expose yourself to it and see what it is really about. What the issues they are really talking about, and deal with what’s really there rather than this demonized notion of guys running about trying to screw little boys. I would have been so much happier as an adolescent if NAMBLA had been around when I was 9, 10, 11, 12, 13.

It is impossible for me to make an accurate assessment of these remarks without seeing the newsletters in question or knowing exactly what Delany was involved with as a nine-year-old. However, the fact remains that Delany is speaking approvingly of publications put out by NAMBLA, the North American Man-Boy Love Association—part of the pro-paedophile movement. The same year that Delany made these comments, gay activist Richard J. Rosendall penned a far harsher assessment of the NAMBLA newsletter.

Delany’s statement is deserving of interrogation, and interrogation is what it received in 2014 thanks to author Will Shetterly. Shetterly’s conversation with Delany can be seen here; it is long and nuanced, and I fully encourage my readers to peruse the discussion in its entirety.

During the interview, Delany clarifies that his positive comments about NAMBLA were directed at the group’s newsletter as it existed in the early nineties, and he distances himself from any of NAMBLA’s subsequent activities. He describes the publication as “a smart, well-written and well thought-out gay rights newsletter” and credits it with advocating humane treatment of children apprehended by the police: “The way children were treated in [abuse] situations… immediately removed from their homes, placed in public institutions, given no counseling when they were most vulnerable and most in need of emotional support, was not a pretty picture.”

So far, these thoughts do not seem entirely outrageous. Delany frequently returns to his earlier concerns about children mistreated by the legal system; for the most part he is rethinking the concept of children’s rights from a libertarian point of view, mistrustful of the state: “in patriarchal society we never give children positive rights—only negative ones. That is to say they are ‘protected’ (by the state) and the administrator of those rights is always the parent.”

But at the same time, Delany repeatedly turns to a far more troubling line of thought by raising the possibility of healthy sexual relationships between adults and children. He claims that “Many, many children are desperate to establish some sort of sexual relation with an older and even adult figure” and states that “there were myriad child/adult pairings, at least in the gay world; the vast majority of them that I knew of or had been involved with as a child appeared to me benign.”

This disturbing thread culminates in a description of a sexual encounter that Delany had as a six-year-old in 1948:

In his cellar, a twenty-five to thirty year old [building superintendent] was masturbating. Me and another friend snuck in to watch. He realized we were there, called to us to ask if we wanted to come out and see what he was doing. We all sat together on his army-style cot. And at his invitation, we touched him—both me and Johnny at six were definitely gay. In the cellar with the super, both of us had erections. We took out our genitals and showed them to him. He touched us, and told us we would probably grow up to be big men.

Delany concludes that it would have been “gross injustice” to prosecute this man. I am far from convinced. While it may be true that Delany and his friend suffered no psychological harm from the encounter, it is nonetheless the kind of experience that could be very damaging to a child—hence why such behaviour should be sternly forbidden under harsh penalties.

Nowhere in the interview does Delany come to a definite conclusion; he never suggests any kind of solid legal reform, but rather gestures towards broad philosophical reconsiderations. I find the disparity between the vagueness of his arguments, and the seriousness of the subject that he is discussing, to be greatly uncomfortable.

So, I would argue that Eness has picked an entirely reasonable target in Delany’s attitude towards childhood sexuality. And what does he do upon picking that target?

He uses it as an excuse to go after John Scalzi.

The third part of the series, “Leaders in Silence,” takes aim at conventions’ anti-harassment policies. Eness quotes from a boilerplate document, used by multiple conventions, that explicitly forbids “uninvited sexual attention,” “uninvited physical contact,” and “intimidation, stalking or following.”

The argument put forth by Eness is that this policy contains a loophole where minors are concerned: it forbids unwanted sexual advances, but says nothing about instances in which paedophiles may convince impressionable children that their advances are wanted.

The article may possibly have the beginnings of a point here—but did Eness, or Vox Day, or anybody in their circle, raise this objection at the time the policies were being written? If not, then why did they wait so long to make an argument that they apparently find so crucial?

Eness then goes off in a very strange direction. He tries to personally blame John Scalzi for any shortcomings in the anti-harassment policy (or the “Scalzi Safe Space Policy,” as he refers to it) simply because Scalzi had previously linked to examples of similar policies with approval. Eness then brings up Delany again, seemingly insinuating that Scalzi and Delany conspired to create an anti-harassment policy that allows paedophilia:

In other words, a pedophile with the Delany mindset is given carte blanche under the Scalzi-endorsed code to attract children “desperate to establish some sort of sexual relation with an…adult figure” for invited sexual and physical attention.

[…]

Scalzi’s desire for his friends’ and fans’ safe place becomes a nightmare if just one of those friends or fans happens to be a molester like fellow SFWA member Ed Kramer, who attracted children to his hotel room at the conventions he ran. You value what you protect, and Scalzi’s “Safe Space” policy affords protection to the pedophiles in SF, both known and unknown, and their accomplices.

To reinforce this line of thought, the article quotes from Will Shetterly’s interview with Delany in which the latter discusses child sexuality. Eness neglects to mention that the interview was posted in July 2014, a year after the “Scalzi Safe Space Policy” was published. Again, who on the side of Day and Eness was raising these concerns in mid-2013, when the policies were first issued?

When Vox Day blogged about the subject of anti-harassment convention policies at the time, he spent a lot of space poking fun at Scalzi but never expressed fear about paedophilia. His commentators were similarly unflustered: “There’s an ‘anti-harassment policy’ everywhere, and it’s called the law,” wrote one.

Eness returns to Delany in the fourth chapter, “The Samuel R Delany Problem.” Curiously, earlier versions of the series announced that the fourth instalment would be entitled “The Texts and Historic Timeline.” When it went live, however, the chapter focused on a single text: Delany’s novel Hogg, completed in 1973 but unpublished until 1995.

Hogg is a deliberately repugnant story about an eleven-year-old boy who falls in with a rape gang led by the titular Hogg, nicknamed in reference to his life of pig-like excess. It is a troubling novel—but then, as Delany himself says, “Hogg is a story written to trouble.” When asked by an interviewer if the novel endorsed the atrocities committed by Hogg’s gang, Delany replied in the negative:

I

feel a little odd talking about a novel as “endorsing” anything. Always, I’ve felt that novels were fundamentally records – and necessarily distorted records – of things observed in the world. […] My like or dislike of them should be of secondary, or even tertiary importance.

In search of a juicy tabloid scoop, however, Eness decides to ignore such nuance and instead presents the novel as being Delany’s manifesto for acceptable sexual relationships.

“[T]he satanic Hogg…gets away with it,” complains Eness, pushing the Comics Code-esque notion that a fictional wrongdoer must always be punished. But the truth is that Hogg has a very clear message: that abuse is a vicious cycle, as we see when Hogg is revealed to have been molested by his father. This scenario relies on Hogg being the result of fundamentally unjust circumstances; it would defeat the object were Hogg to be given a just punishment.

Eness includes a series of quotations from various prominent SF authors in praise of Delany. Each of these statements is followed by a repulsive passage from Hogg, as though the commentators are specifically praising this particular novel, or that Hogg is typical of Delany’s writing (“Hogg is only one of Delany’s sadistically abusive ‘pornographic’ novels,” claims the article).

In reality, however, none of the quoted authors are talking about Hogg—except perhaps Jo Walton, who states that “I find [Delany’s] pornography very difficult to read.” The words of praise are presumably directed at Delany’s better-known novels, such as Babel-17 and The Einstein Intersection. Through a crude sleight-of-hand, Eness implies that anyone who admires Delany’s writing must, by extension, endorse the rapes and murders committed by Hogg’s fictional gang.

“The Samuel R. Delany Problem” is illustrated with a still from Victor Salva’s film Clownhouse; below this is a caption discussing Salva’s rape of a preteen boy. The relevance of this crime to Delany’s career is never established; not content with smearing Delany’s fanbase as latent sexual predators, Eness appears to associate them with the rape committed by Salva.

The final chapter in the series, “The Victims,” is something of a miscellaneous round-up. It goes into more detail about the crimes committed by Breen, Bradley, Kramer and Salva. It reposts a comment made on Jim C. Hines’ blog, from an individual offering the reasonable argument that Hines was spending too much time criticising Larry Correia’s right-wing opinions and not enough discussing the Marion Zimmer Bradley scandal or Delany’s views on NAMBLA. It concludes its overview by talking about Heidi Saha, a cosplayer of the 1970s who spent her early teens dressing as female characters from fantasy iconography; then, as now, this generally entailed wearing something skimpy.

In a rare moment of positivity, Eness praises Nancy A. Collins for boycotting Kramer’s convention Dragoncon. The feeling is not mutual, however: “As for the Castalia House group, I did not see them on the ramparts during the Dragoncon Boycott,” writes Collins. “Well, since [Day] knows he’ll never win a Hugo, he’s got to punish fandom somehow.”

If we wade through the smears and insinuations, there are some fair points in “Safe Space as Rape Room.” But all of these good points can already be found in Will Shetterly’s writing on the subject of paedophilia in the SF community. All Daniel Eness has done is bastardise Shetterly’s work for the sake of attacking Vox Day’s opponents.

It is impossible to say exactly how much input Day had into the series, but Eness is clearly toeing Day’s party line: just look at how the essay repeats Day’s lie about Scalzi being an admitted rapist. Also interesting is how both writers nonsensically equate opposition to the racism of H. P. Lovecraft with support for Bradley’s paedophilia. Day, reporting Bradley’s crimes, asked whether “the pinkshirts who have been so eager to read out H. P. Lovecraft, R. E. Howard, and Orson Scott Card from the genre will be as ready to eliminate the bisexual, child-molesting neo-pagan Marion Zimmer Bradley from it as well.” Eness, similarly, starts his essay on child abuse by invoking Lovecraft’s detractors:

As the World Fantasy Award abandons its iconic image and founding inspiration – H. P. Lovecraft – the obvious question is, “How can such an esoteric and minority voice get away with such a crime against their organization’s own interests?”

Most telling of all is how the essay completely ignores Vox Day’s notorious comments about Anders Breivik. Eness goes out of his way to present the likes of Isaac Asimov and John Scalzi as dangers to children, but somehow neglects to mention Day’s disturbingly sanguine response to the murder of defenceless 14-year-olds. “Safe Space as Rape Room” comes across as an attempt to smear the rest of the SF community so that Vox Day looks better by comparison.

If the essay is nominated for a Hugo, then judging by last year’s results, it will end up behind “No Award.” Vox Day, of course, will take this as proof that his accusations are warranted. This, then, was what he had in mind when he predicted that the Sad Puppies’ opponents would be publicly associated with paedophilia.

Vox Day Sings the Blues

Reading Vox Day’s outrage about degenerate art, it is easy to question his sincerity. Certainly, it is curious that a person could be so upset by the rape of an entirely fictional teenager in “Equoid” and yet so complacent about the murder of real-life teenagers at the hands of Anders Breivik. How much of his behaviour is some kind of act—the element of performance that is part and parcel of Internet trolling?

If Vox Day truly is a “Cruelty Artist,” then his masterwork is almost certainly himself. He has thrown away any hope of a good reputation and is destined to be remembered primarily as an oddity in science fiction history. I can readily imagine him ending up on the same shelf as Richard Shaver (only without the curiosity value) and L. Ron Hubbard (only with less financial success).

Having earned the reputation as SF’s Satan, his only response is to try and demonise those who have condemned him.

Vox Day’s parting words to science fiction will be “I know you are, but what am I…?”

Vox Day has proven himself as someone not to listen to under most circumstances, but this is a good take on destroying his and his cronies’ arguments while acknowledging when his stopped clock can be right, so to speak.

The idea that he’s criticizing the liberal part of sci-fi/fantasy through Bradley is wacky, though. All the condemnation I’ve seen of her has come from that part of fandom. (As for reading her books in light of her and her husband’s crimes, to my mind she’s dead, as is Lovecraft, who I sometimes read. BUT I think whether to read her or not because of those crimes is a choice you make as an individual and for your own reasons.)

Great article.

Dear…gods. And I thought Frank Miller was FUBAR…